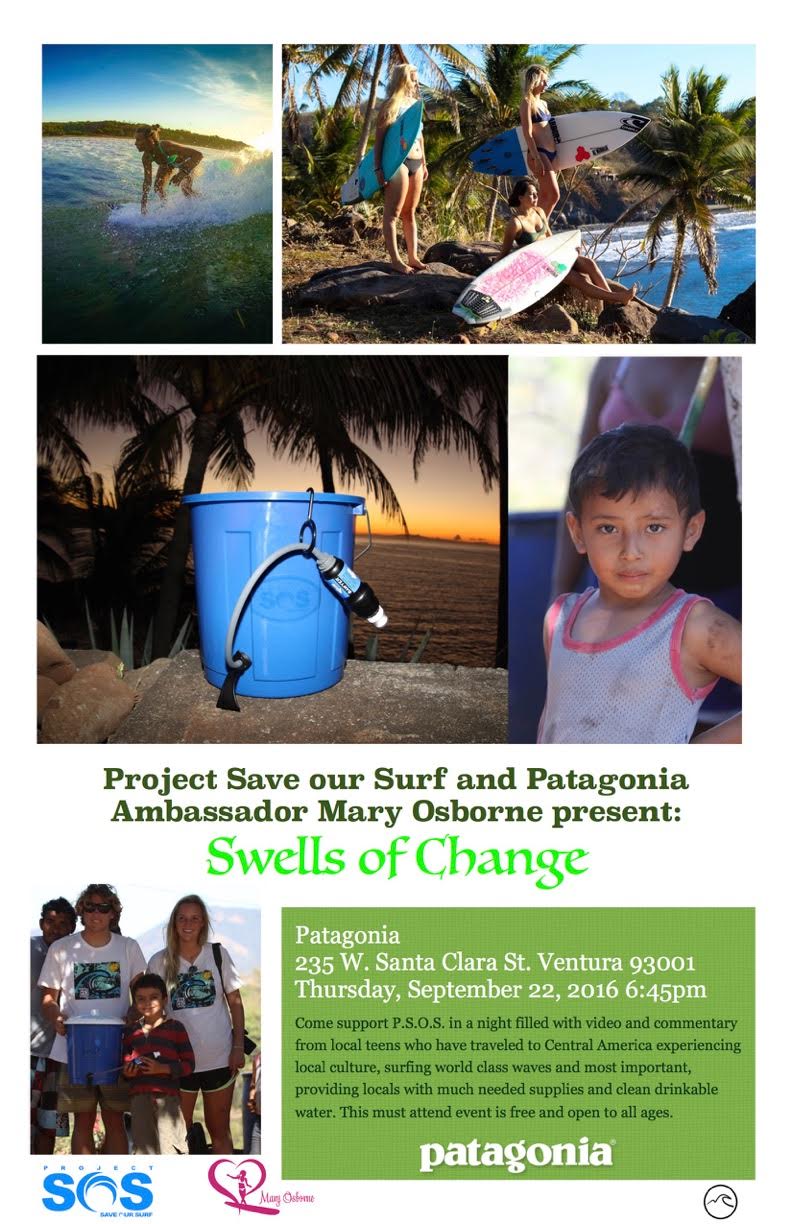

Project Save Our Surf and Patagonia Ambassador Mary Osborne present: Swells of Change

Come support P.S.O.S. in a night filled with video and commentary from local teens who have traveled to Central America experiencing local culture, surfing world class waves and most important, providing locals with much needed supplies and clean drinkable water. This must attend event is free and open to all ages.

Patagonia

235 W. Santa Clara Street Ventura 93001

Thursday, September 22, 2016 6:45pm

PSOS Water Filter Project- Ben Tre, Vietnam

Project Save Our Surf Director, Karon Pardue and Ambassador, Mary Osborne, travel to Vietnam to deliver water filters to Ben Tre Provence:

Not a second goes by without hearing the sounds of scooters honking throughout the streets it’s a nonstop parade of scooters weaving in and out of people, cars and colorful vendors. Some holding three or four bodies, others loaded up with fresh farming greens and livestock. Crossing the street for a pedestrian can be a petrifying and exhausting game of Frogger. We grab each other tightly as we dance once step forward, two steps back, until gaining enough courage to quickly leap across the foreign busy streets of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

I was asked to join my close friend Karon Pardue, Vice-President of Project Save Our Surf foundation on a water filter project in Vietnam. I had never been to Vietnam nor was it on my bucket list of places to visit. I knew nothing about the country, minus history of the war and the small bits shared from my Vietnamese salon girl I took surfing one summer. I have a crazy passion for three things in life: surfing, traveling and children. The more I began to think about embarking on this adventure, it only made sense for me to accept the offer and join PSOS.

Before I knew it, Karon and I embarked on a 21-hour plane flight to Ho Chi Minh City. Along with the help of a global organization, SOS Children’s Villages International, our goal was to set up 50 water filters in the Ben Tre Provence of Vietnam. Located in 133 countries and territories, SOS is known for helping local children and families with care, education, and health. Similar in name and both fantastic organizations, it was an ideal collaboration for PSOS and SOS.

About Ben Tre

Ben Tre is a city in southern Vietnam, along the Mekong Delta. Traditionally, people living in here have earned a living from agriculture, forestry and rice farming. This area has one of the highest child poverty rates due to a number of unfavorable factors: social inclusion and protection of children, infrastructure, education, housing, and child labor rates. With some success, government initiatives have sought to reduce these concerns, but these major components still encompass the entire region

With 2,360 rivers totaling to more than 10km, it would appear that Vietnam should easily provide copious supply of water to the nation. Unfortunately, with a 6-7 month dry season and the country’s coastal location, Vietnam is highly susceptible to natural disasters such as typhoons, storms, and floods. Just these two issues alone effects conditions that play an important part on indigenous people, their livelihood, agricultural lands, livestock, and their infrastructure.

While studies have shown the quality of upstream river water is generally much less risky, downstream sections of natural water sources (lakes, rivers, canals) reveal poor water quality and are still very unsanitary. Today, urban villages still use surface water from shallow dug wells, while rural areas use groundwater pumped in from treatment plants. Both have detected highly contaminated health risks— exposure to diarrhea, malaria, bacterial infestations, arsenic, manganese, selenium, barium and other major toxic substances. For many families in Vietnam, just one simple water filter can make a world of difference and, most importantly, prolong life.

SOS Orphanage Village

After a three-hour drive south of the city, Karon and I finally arrived at the SOS Children’s village. The perfectly groomed grass and gorgeous Plumeria trees surrounded twelve petite family orphan homes. We could hear a lovely chorus of happy youthful voices simultaneously vibrating throughout the village walls. Out walked a sophisticated gentleman with a warm smile, Mr. Huco Bi, the head of the SOS Orphanage.

The SOS Children’s Village in Ben Tre is located roughly 50 miles south of Ho Chi Minh City. Each home is built in the architectural style typical of the region, with the roofs covered in red tiles and brick walls. The village has a special designed nursery and a school for 1,000 primary and secondary level pupils. It even offers a vocational training center to provide practical training and support for young adults hoping that one day they can eventually live independently in the villages nearby. This might sound strange, but if you had to be an orphan in Vietnam, you can’t get better than being in the care of SOS.

Walking throughout the village, Karon and my light colored skin and bleached out hair made the children curious and gitty. They wave, smile and stare, as many have never seen a Westerner in their lifetime, many haven’t have not. With the help of Mr. Huco BI and the SOS team, Karon and I carefully show the older teens how to assemble the water filters and drink from the big yellow bucket. Perplexed by not having to boil their water before drinking, it was apparent children’s first sip of clean water was a huge success. Not one person gagged, spit it out or ran away. Just giant smiles filled the room while a large line of children and SOS workers gathered to taste something as simple as purified, clean and safe water.

Visits to remote SOS Villages

With every visit, Karon and I are escorted into 6 various villages by top local officials. At every home the head of the each household politely sits us down, pours boiling hot tea that tastes like fresh hay in tiny glass teacups and begins to share their life story. Each story is enough to make your heart skip a beat and tears slowly fall down your face. Many parents have lost their significant loved ones and are raising multiple children. Some have adopted young children where the parents left them behind. Many of the people we met were disabled, extremely poor, and had what they called “Spirits” disease. Yet, somehow each village remained positive, strong and work together as one giant family nucleus. Karon and I can’t understand a lick of Vietnamese but the obvious lucid expression in everyone’s eyes evoked a mass amount gratitude, hope and thankfulness. The video itself says a thousand words.

Going Coastal

“One, two, three… Get up, Dian.”

After a long scary 4-hour drive to the coast of Vietnam, we found ourselves on what is called the “Back Beach.” Seeing the coast was a big breath of fresh air that Karon and I needed after spending an emotional in few days with families in the villages. Karon was in heaven scowling the beach for rare shells, while I searched the vendors for a surfboard to play on. Randomly, I stumbled upon the coastlines only “Beach Bar” full of wind surfing, stand up paddle boards and a few rustic surfboards.

For about $10US dollars I rented the biggest board I could to teach our guide to surf. The brown hued ocean was comfortably warm and the 1-2 foot waves were barely big enough to catch a proper ride. The minute I caught my first wave people were watching in awe. Our guide Dian, was a complete natural getting up on his first wave riding all the way to shore. He was immediately hooked. One by one I used sign language and rotated out the locals for a try. Yelling, laughing, and clapping hysterically, surfing was definitely a hit here on Back Beach. I’m pretty confident the Beach Bar’s sales dramatically increased that afternoon.

Western Bound

Like most good trips, it’s unfortunate when they have to end. Loaded up with bags full of souvenirs, unforgettable memories and new profound emotions, Karon and I packed our belongings and embarked on the long journey back to the States. We both are so grateful to have touched the lives of so many and are honored to represent PSOS, SOS and the country of Vietnam. Whether it is by donations, prayers or simply following this adventure via social media, Karon and I can’t thank everyone enough for being apart of this water filter project. Who would have thought just a simple glass of clean water could change a person’s life forever?

Cheers!

5 Gyres is Cleaning Up Our Waters One Microbead At A Time

Early into Mike Nichol’s 1967 film “The Graduate,” Dustin Hoffman’s character receives some unsolicited post-grad advice: “One word: plastics … There’s a great future in plastics.”

Even then, audiences couldn’t have imagined what a prophecy that was. Plastics, designed for short-term use and originally marketed to the 1950s housewife as a panacea for dishwashing, paradoxically last indefinitely. Today, about 300 million tons of plastic are produced globally each year, and only about 10 percent of that is recycled. Of the plastic simply trashed, about a quarter million tons ends up in the sea is floating in the sea.

But the accumulation of plastic waste doesn’t exist in the Great Pacific garbage patch or garbage zoo we’ve come to believe – it’s something more insidious.

“The best name for it is a plastic smog,” said Marcus Eriksen, lead author on a paper published earlier this year in the Plos One journal that served as the fist estimate of how much trash and plastic is floating in the world’s oceans. Eriksen is co-founder of the Santa Monica-based nonprofit 5 Gyres, along with his co-founder wife Anna Cummins.

About 92 percent of the 5.25 trillion particles of plastic in the sea are the size of a grain of rice or smaller, Eriksen said, and “what happens when trash gets near coastlines, on every coastline worldwide, sunlight or fish will reduce a plastic object to confetti very quickly.”

But the worst offender of plastic waste in the water doesn’t come from the bottles, six-pack rings, or bags. The biggest problem is actually the tiniest product: microbeads, found in face wash, body scrub, moisturizer, and toothpaste.

UN Environmental Ambassador

Watch Mary as she talks about her 5 Gyres experience as a UN Environmental Ambassador. Spending 33 days at sea in an effort to mitigate the ocean pollution issues we face today.

Klean Kanteen

It was announced: Mary Osborne is the new Klean Kanteen advertisement that supports 1% for the Planet, and the 5 Gyres team. This photo was shot while on a 33 day expedition with the 5 Gyres crew. The talented team of scientists and environmentalists along with Mary were one of the first boats to explore the South Atlantic gyre system.

Bali: Green Essence

Story and Photos by David Pu’u

In the past few years, it seems that everyone has turned toward green. In fact, the color has become a necessary branding indicator for everything from chain stores to politicians, and sometimes one with little significance. It is certainly a pity that the green movement has come to this, but here is why. In the hard light of day, people are what matter. We are one of the few entities on this spinning ball with the power to mitigate our effect. But where does one begin?

Look in the mirror. It must begin with the individual. The Laws of Exponentiality and the tenet of Ephemeralization, which was expounded on by Buckminster Fuller in 1938, basically say that we ought to be able to do more with less. This really is the key to going green. Unfortunately, it is the polar opposite of capitalist commerce and most political systems of governance.

That is what made the trip to Bali by Donna Von Hoesslin, owner of Betty B’s in Ventura and my girlfriend, and some of the women on her team a fascinating concept. Here you had a capitalist—a businesswoman—determined to create some positive change by being truly green. She resolved to invest in socially sustainable projects in a developing country that would supply her company with ethically made, yet price-competitive products.

We had met David Booth, a former British civil engineer with the World Bank, a few years back. Booth basically retired to Bali, where he founded and developed an NGO called the East Bali Poverty Project (EBPP).

The group of us embarked on the trip to Bali in an effort to give back and to explore additional methods of bringing commerce to the people Booth had literally dedicated his remaining years of life to saving and putting on the path to an economically, culturally and ecologically sustainable future.